Many community banks invest in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods to make lasting impacts while also getting Community Reinvestment Act, or CRA, credit. This work to aid and rebuild communities is the direct result of the close ties community banks develop with the people they serve. Here’s how three community banks are making powerful investments under the CRA.

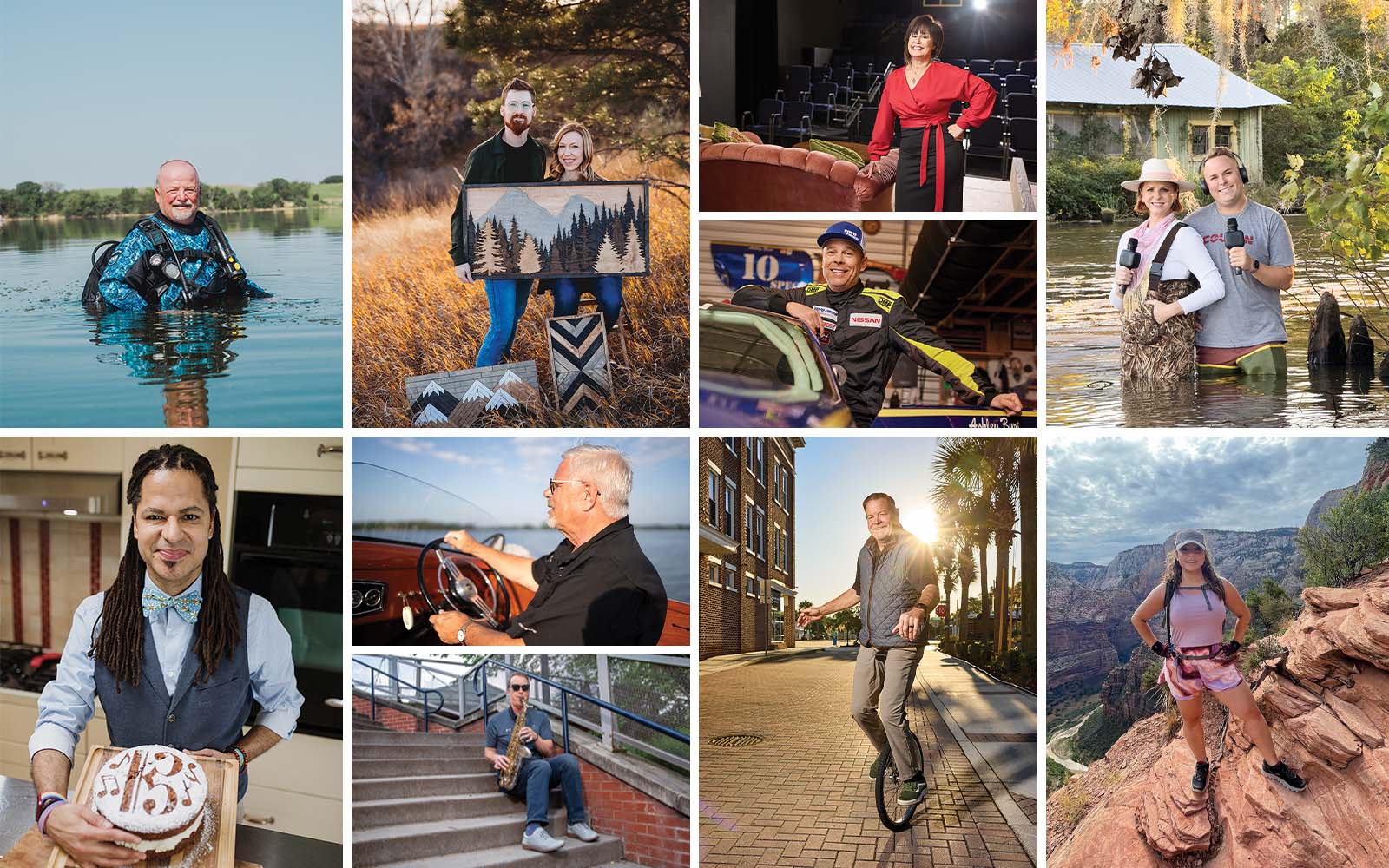

3 banks investing in communities under the CRA

October 01, 2020 / By Colleen Morrison

Many community banks invest in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods to make lasting impacts while also getting Community Reinvestment Act, or CRA, credit. This work to aid and rebuild communities is the direct result of the close ties community banks develop with the people they serve. Here’s how three community banks are making powerful investments under the CRA.

The civil unrest that has marked 2020 underscores the importance of making lasting investments in communities and actively building trust with consumers.

For many community banks, strategies to fulfill Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) requirements include funding community development and banking low-income areas. Like other compliance issues, meeting these conditions factors high on the list of priorities for community banks.

“We would not be successful if it weren’t for the support of our community,” says Chris Courtney, president and CEO of $1.4 billion-asset Oak Valley Community Bank in Oakdale, Calif. “We have to give back not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because we owe it to the community.”

Here, we look at how three community banks take issues like housing affordability, homelessness and poverty head-on by investing in their communities, collaborating with local organizations and more. Through this work, these banks are also achieving CRA excellence.

Oak Valley Community Bank fights homelessness

For Oak Valley Community Bank, the goal is to set a standard that exceeds regulatory expectations around CRA by living the true spirit of community investing. Oak Valley Bancorp operates Oak Valley Community Bank and its Eastern Sierra Community Bank division, serving six counties in rural California.

Within its footprint, the poverty level exceeds the national average by up to roughly four percentage points (15.6% in Stanislaus County in 2018 versus a national average of 11.8%), so much of the work it does focuses on creating sustainable social improvements in its local environment.

For example, homelessness often goes hand in hand with a high poverty rate. In 2019, Stanislaus County faced a record-high homelessness rate, with nearly 2,000 unhoused people—an increase of 42% on 2018.

To combat this trend, Oak Valley Community Bank donated to Modesto Gospel Mission to provide resources that met immediate needs but with an eye on future recovery. Initiatives like life skills classes, employment training and assistance, addiction recovery and medical clinics helped community members get off the streets.

“Through in-person outreach, Oak Valley strives to understand the needs of the community in order to build things up and make our communities better,” Courtney says. “We don’t just treat the symptoms; we’re attempting to treat the root cause in our communities. If we do that, we have impact not just today but down the road.”

Case in point: Oak Valley Community Bank invests in several community foundations, including the Stanislaus Community Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization in Modesto, Calif., dedicated to improving the lives of Stanislaus County residents. The community bank has been supporting the foundation’s efforts to inject operational support into the most vulnerable organizations and nonprofits in the area.

“I’m most proud of our work with the Stanislaus Community Foundation,” says Jose Sabala, Oak Valley Community Bank’s vice president CRA officer. “They are very innovative in the community development world. We are deeply proud of our community revitalization efforts.”

Beyond these initiatives, the bank has supported more than 1,600 community development service hours in support of other community activities, including bringing a financial literacy program to six high schools within the bank’s assessment areas.

“It’s about getting on the ground and holding hands with your community to see what you can do as a community banker,” Sabala says. “It’s about uplifting the community we serve.”

WesBanco’s CRA-focused culture

For WesBanco Bank Inc., a $15.7 billion-asset community bank in Wheeling, W.Va., that sentiment of service pervades the culture. Just ask LaReta J. Lowther, senior vice president and director of community development and CRA compliance, who has been with WesBanco for 40 years. She built its CRA program from the ground up.

“Our president and CEO, Todd Clossin, has this missive that he uses: ‘We do well by doing good.’ When you have that kind of leadership in an organization, achieving the ‘Outstanding’ CRA rating is just easy.”

—LaReta J. Lowther, WesBanco Bank

“The most important factor is that [CRA support comes] from the top down,” Lowther says. “Our president and CEO, Todd Clossin, has this missive that he uses: ‘We do well by doing good.’ When you have that kind of leadership in an organization, achieving the ‘Outstanding’ CRA rating is just easy.”

Though WesBanco has a six-state footprint, giving back to the individual communities it serves is customized to each market. For example, as COVID-19 began to wreak havoc, WesBanco initiated its first-ever grant program. Using the interest earnings from the WesBanco Bank Community Development Corporation New Market Loan Program, the bank funded a grant program dubbed the Community Partner Relief Fund, which was designed to provide $350,000 in resources to nonprofits throughout the footprint. These grants would serve vital programs addressing food insecurity, meal delivery for the homebound, personal protective equipment for health clinics and first responders, homeless shelter supplies, and educational school supplies to help students who had to attend class online.

Wasting no time, WesBanco launched the initiative on March 18 and, within hours, the phones were ringing off the hook with people asking how to apply. By April 4, the bank had received 235 applications requesting a combined $1.3 million.

“I really thought we might get 50 applications,” Lowther says. “That just shows you the amount of need that was out there during this pandemic.”

Despite the overwhelming demand, the community bank was able to fund 137 organizations before the pool of funds ran dry. But that didn’t stop the team. “This year is the 150th anniversary of the bank, so we were going to have a big celebration and do different activities in each community, but the pandemic kind of put things on hold,” Lowther says. “So, the employees decided to reallocate those funds and provide an additional $200,000 to fund even more nonprofit organizations. Altogether, it was over a half a million dollars that we were able to fund nonprofits for emergency relief during the pandemic.”

That additional round of grant money was distributed in increments of $20,000 to each of the bank’s 10 markets. Lowther played the role of the overseer, ensuring a variety of organizations across each community received funding.

“About 60% of grants were for food banks, emergency housing [and] building emergency shelters for the homeless so they could practice social distancing and wash their hands,” Lowther says. “It was very eye-opening and rewarding. I’ve been at the bank for 40 years, and this was one of the best projects I’ve ever been involved in.”

ICBA is active on CRA reform

With the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), ICBA believes consistency is the central word. For years, ICBA has advocated for CRA reform to include:

Fair, equitable, consistent and transparent implementation of the rule

Comparable regulations among the agencies, with a uniform CRA rule

Standardization in CRA examinations among examiners and agencies

An increase in asset thresholds defining “small,” “intermediate small,” and “large” banks

An illustrative—but not exhaustive—list of activities that are presumed eligible for CRA credit

Incorporation of credit unions, fintechs and any financial firm that serves consumers and small businesses into CRA requirements

The ability for community banks to define their assessment areas and opt into a metric-based approach or use the existing CRA framework.

Given developments with the OCC’s rule (see “Efforts to modernize the CRA,” page 51), some of these criteria are being met, while others are further complicated. For example, ICBA supported Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) provisions that allow community banks up to $2.5 billion in assets to remain under the existing CRA framework. However, ICBA made the point that the framework is complex and imposes new and excessive data-collection costs on community banks.

“Many community banks won’t even be close to triggering deposit-based assessment areas,” says Mickey Marshall, ICBA’s director of regulatory legal affairs. “But the recordkeeping to show that they don’t have to meet this requirement will be a new burden to banks of all sizes.”

Union Bank redoubles its CRA efforts

Bankers realize the rewards that come from serving the community. Because, as $870 million-asset Union Bank in Morrisville, Vt., learned, CRA ratings can come and go. After receiving a “Satisfactory” rating in its previous review, the bank doubled down on its efforts to capture an “Outstanding” in 2020. (Coincidentally, this was the first virtual CRA evaluation completed during COVID-19 in the Northeast.)

“[In the exam prior to the most recent exam], we had a ‘Satisfactory’ for the first time, and part of that was that we had entered new geographies and hadn’t had enough time to really gain traction in some of those new geographies,” says David Silverman, Union Bank’s president and CEO. “But we’ve always taken great pride in being ‘Outstanding,’ and maybe getting dropped to ‘Satisfactory’ was a challenge that refocused [us]. We redoubled our efforts.”

In 2019, the community bank invested $1.1 million in the Jeudevine Limited Housing Partnership to fund the rehabilitation of 18 affordable multifamily housing properties. The bank also made two investments totaling $100,000 in Bethlehem Workforce Housing, a Community Development Finance Authority (CDFA) tax credit project in New Hampshire, to support a 28-unit, low-income housing project development.

“The other component is that we documented better,” says Tricia Hogan, executive vice president and senior risk manager for Union Bank. “In the last exam, there was definitely a change in expectations. We had to take a step back and just modify what we were doing in order for it to qualify, so there was a reemphasis on what qualifies and what documentation we needed to show.”

Union Bank also boasts a long-term community program, Save for Success. Introduced in the mid-90s, this program makes savings front and center for 40 local elementary and middle schools and promotes making saving a habit at an early age. By partnering with volunteer parents, Union Bank hosts a weekly banking day at the school, and students can bring in their money to deposit. The parents act as tellers, depositing the money on the students’ behalf. The kids have a passbook that marks their deposit, and the parent-tellers stamp their book and then facilitate the actual deposit. It’s going to the bank without the actual trip to the branch.

“That program has been going on for so long that we’re now making home loans and business loans to the graduates,” Silverman says. “The kids really love the program; the parents love the program. It’s one of my favorite things we do.”

“If the CRA was not in place, we’d be doing the same activities. The only difference is now we document them.”

—Tricia Hogan, Union Bank

Community banks’ impact

From supporting healthy savings to helping homeless in the community, these case studies provide insights into the breadth of potential CRA activities, but they offer only a glimpse of the impact community banks can have on the areas they serve. In fact, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition reports that more than $2.25 trillion in mortgages has been awarded to low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods and borrowers since 2009, and another $1.2 trillion has been divided among business loans in LMI neighborhoods and small business loans.

With community banks having a presence in 97% of low-income designated counties, there’s a substantial tie between these funds and community bank support.

In light of these statistics and despite the pressures of meeting CRA obligations, community bankers point to the need to serve their customers as the primary driver of their activities—not the regulatory mandate. “If the CRA was not in place,” says Union Bank’s Hogan, “we’d be doing the same activities. The only difference is now we document them.”

Efforts to modernize the CRA

On May 20, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) issued a final rule to strengthen and modernize regulations under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). This rule included, among others, provisions to:

Allow OCC-regulated banks with less than $2.5 billion in assets to opt into the new performance standards or choose to stay within the current framework

Raise the small bank test threshold to $600 million and the intermediate small bank test threshold to $2.5 billion

Introduce significant data collection and reporting efforts. Even small banks that do not opt in to the new framework will be required to track and report the location of deposits.

Create an “illustrative list of nonexhaustive examples of qualifying activities that meet, and may include activities that do not meet, the qualifying activities criteria.”

“Whether you’re an OCC-regulated bank or not, the qualified list gives you creative ideas,” says Mickey Marshall, ICBA’s director of regulatory legal affairs. “Banks should check with their own regulator to see if these options apply.”

Notably, when it was put out for comment, the proposed rule was issued jointly with the FDIC, but that regulator chose to step back from final rulemaking. The Federal Reserve has expressed interest in modernization efforts, offering an alternative to the OCC approach back in January and stating, “It is more important to get the reforms done right than to do them quickly.”

“The current CRA framework is more than 20 years old,” Marshall says. “There is interest in modernization, and we’re staying in communication with regulators on this issue.”

Subscribe now

Sign up for the Independent Banker newsletter to receive twice-monthly emails about new issues and must-read content you might have missed.

Sponsored Content

Featured Webinars

Join ICBA Community

Interested in discussing this and other topics? Network with and learn from your peers with the app designed for community bankers.

Subscribe Today

Sign up for Independent Banker eNews to receive twice-monthly emails that alert you when a new issue drops and highlight must-read content you might have missed.

News Watch Today

Join the Conversation with ICBA Community

ICBA Community is an online platform led by community bankers to foster connections, collaborations, and discussions on industry news, best practices, and regulations, while promoting networking, mentorship, and member feedback to guide future initiatives.