Community banks with deep roots and pride in their Native American heritage are committed to providing financial assistance, housing aid, lending and educational outreach to underserved tribal communities across the United States.

How these community banks support Native communities

November 01, 2022 / By Ed Avis

Community banks with deep roots and pride in their Native American heritage are committed to providing financial assistance, housing aid, lending and educational outreach to underserved tribal communities across the United States.

Quick Stat

18

The number of Native American-owned banks and CDFIs in the United States

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

The per capita income of residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota is about $7,800, a staggering 57% below the national average, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Similarly, the unemployment rate far exceeds national averages, and the high school graduation rate of Native Americans in South Dakota is less than 50%.

It’s no surprise, then, that the mission of Native American Bank, which serves customers on the Pine Ridge Reservation and in many other parts of the country, extends deeply into job creation, business financing and financial literacy.

“If you look at where we do business and where we go, it’s some of the poorest areas of the country,” notes Tom Ogaard, president and CEO of $230 million-asset Native American Bank, which is headquartered in Denver. “The challenges that various tribal governments and tribal nations face are devastating for some and very challenging for others.

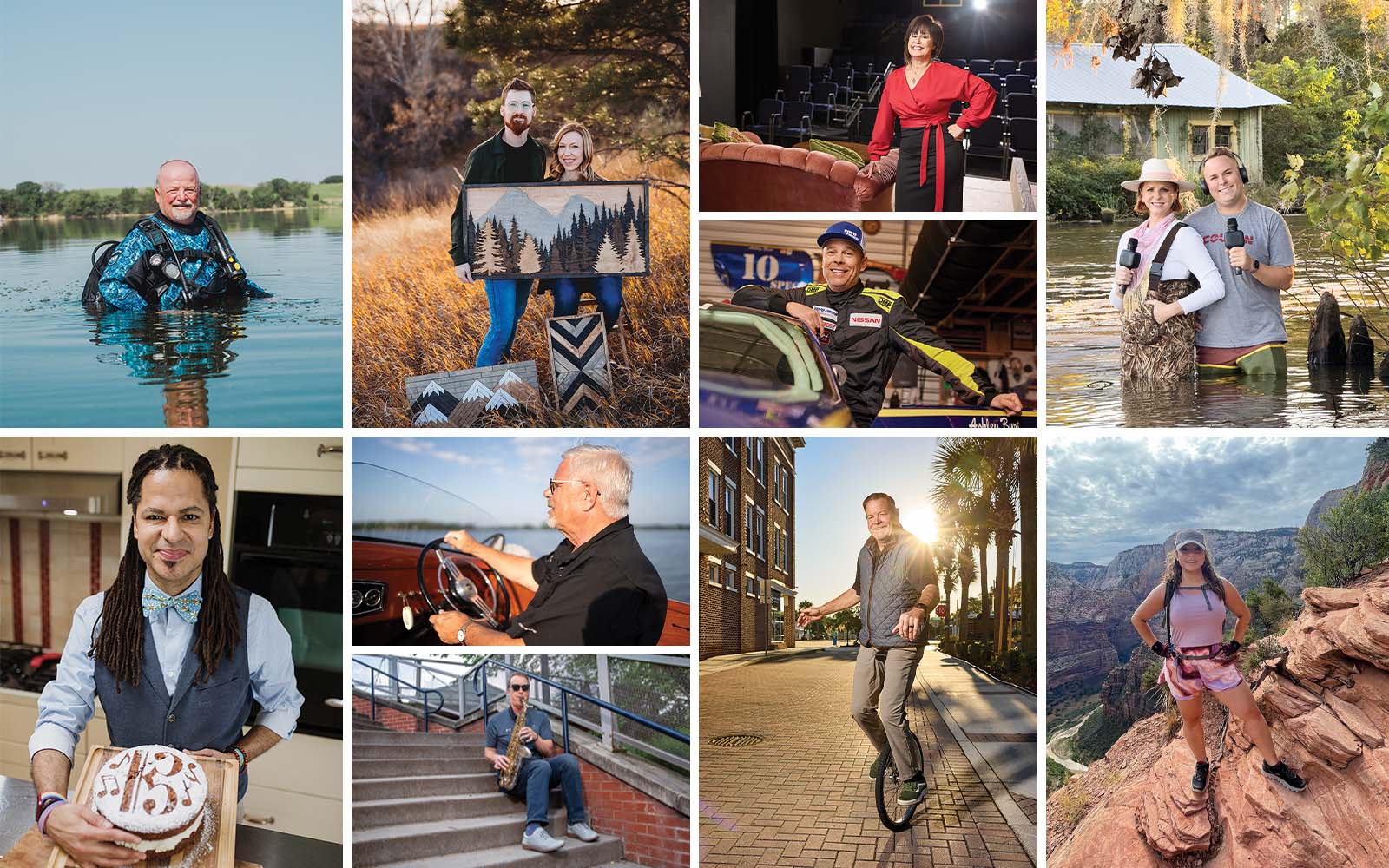

Native American Bank provides business lending toward healthcare in reservations across the country. Tribal members gather to set up for the celebration and ceremonies to commemorate breaking ground on a healthcare facility.

“Part of our work is to provide not just economic diversity but also to create jobs and sustain jobs. Along with that goes financial literacy and other types of support that we can provide so individuals and entities can get comfortable working with a bank.”

Native American Bank is one of a handful of ICBA member banks that provide financial assistance to Native Americans and the institutions that serve them. Often, these community banks serve the community at large as well, but they are rooted in service to Native Americans.

“The challenges for a lot of the Native communities are formidable,” Ogaard says. “There are so many roles that need to be filled and so many opportunities to provide support that any one bank just can’t do it alone.”

“It was always unsettling that the first people here owned homes at the lowest rate of any demographic in the United States. And so, the bank really sought out to be a leader in that, and we certainly have been.”

— Josh Pape, Chickasaw Community Bank

Investing in homeownership

Housing in many Native American communities, whether on reservations or in non-reservation communities, is in serious need of investment. A 2017 report from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimated that 68,000 units of housing were needed to replace “severely inadequate units” and reduce overcrowding in tribal areas.

Consequently, providing home financing is one of the key roles Native American banks play. And much of that involves creatively sourcing funds and helping Native governments leverage them.

In fact, the governor of the Chickasaw Nation, Bill Anoatubby, had a mission to provide capital in Native land, where it was scarce. That was a key reason Chickasaw Community Bank was founded in Oklahoma City, Okla., in 2002, says Josh Pape, Oklahoma City market president for the $418 million-asset community bank.

“The bank really wanted to be a leader in providing home ownership, the cornerstone of the American dream, to Native Americans,” Pape says. “It was always unsettling that the first people here owned homes at the lowest rate of any demographic in the United States. And so, the bank really sought to be a leader in that, and we certainly have been.”

Chickasaw Community Bank regularly volunteers with Habitat for Humanity. Last year, it sponsored and dedicated a home to someone in need.

Pape explains that Chickasaw Community Bank has originated more than $1 billion in home loans and is currently servicing more than $1 billion of mortgages for Native American homeowners.

A key tool for Chickasaw Community Bank and others serving Native American communities is the HUD Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program. This program, established in 1992, guarantees home loans to American Indian and Alaska Native families, Alaska villages, tribes or tribally designated housing entities. It also allows for a down payment of just 2.25% and flexible underwriting.

“The HUD 184 loan is primarily for individuals to buy houses, but we also are able to use it for tribes, such as a housing authority building a one- to four-family affordable housing project,” Pape says.

Chickasaw Community Bank’s efforts to improve tribal housing extends beyond the HUD 184 program. Pape says the community bank also uses its expertise to help tribal housing authorities use federal money for larger housing projects than they could do otherwise.

“Tribes are eligible for federal dollars to go towards services and housing for its members, and the bank is familiar with those funds, how they can be used and how they can be appropriately leveraged while remaining in compliance,” Pape explains. “That can help the tribe multiply its funds dedicated to housing efforts.”

One tool HUD provides to tribes is the Title VI Loan Guarantee Program, which was authorized by the Native American Housing Assistance and Self Determination Act of 1996. This program provides a guarantee of 95% of loans to tribes for housing projects and permits the tribes to use a portion of their Indian Housing Block Grant as leverage. The aim is to reduce the risk to the lender and increase the number of units the tribes can build.

Lumbee Guaranty Bank, which serves the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina and the broader community, has provided HUD Title VI loans to the tribe, says Kyle Chavis, CEO of the $506 million-asset community bank, which is based in Pembroke, N.C.

Lumbee Guaranty Bank established a $25,000 endowed scholarship fund at Fayetteville State University to help students meet their academic and career goals.

“We made the Title VI loan to the tribe for housing for tribal members, and it enables them to leverage their HUD funding to service a loan for multiple families’ housing needs instead of using those funds to build individual houses,” Chavis explains.

Commercial lending for tribal communities

Businesses in Native American communities provide jobs and stability, and community banks know how important it is for them to support those businesses.

For example, Native American Bank provided financing for several convenience stores at the Pine Ridge Reservation. One of them doubles as a community center, Ogaard says, so the bank’s support is providing jobs and a place where people can gather.

“One of the other entities that we have supported is a manufacturer of protein bars,” he adds. “It’s not without its challenges, but it produces jobs. And it is a mechanism to demonstrate that even in a place like Kyle, S.D., you can build an entity and work on its success on an ongoing basis.”

During COVID, like most community banks, Native American banks offered Payroll Protection Program (PPP) loans to businesses in their communities. For example, Lumbee Guaranty Bank originated about 600 PPP loans worth $31 million, Chavis says. Those loans—about 35% of which were to Native-owned businesses—saved 4,700 jobs.

Lumbee Guaranty Bank processed those loans manually, Chavis says, and the quick, personal service worked well for it and its borrowers.

“It was a lot of work to handle the process manually, but it ended up being a really good outcome for us, from the standpoint of having all of our loans forgiven,” Chavis says. “We also created goodwill in the community and were able to acquire some relationships from some of our larger competitors because of how we handled the PPP process. It just ended up being a big win for us.”

Government help

Chickasaw Community Bank has tapped the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Indian Guarantee and Insurance Program, which provides a 90% guarantee on loans made to businesses that are 51% or more Native American-owned. Pape says the bank has used that program for loans over the past few years.

As a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI), Chickasaw Community Bank received a grant in 2021, allowing it to lend money to Native American-owned businesses that were affected by COVID.

“We used those funds to create what we’ve coined a Native American revolving loan fund,” Pape says. “We’ve been able to use those proceeds to extend some capital to businesses that may not otherwise be eligible under traditional bank programs. A couple of examples are a trucking company and a home healthcare company.”

As with housing funds, Native American banks sometimes get creative to help tribal businesses leverage anticipated federal dollars. For example, Chickasaw Community Bank loaned money to a charter school whose enrollment is 87% Native American. The school had received a reimbursement grant through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, but it didn’t have the cash to spend to get reimbursed.

“So, we used that Native American revolving loan fund to give them the capital they could go spend, and then when they get reimbursed, that reimbursement comes back in and pays their loan back,” Pape explains.

Some Native American-owned banks do not limit their business lending to a particular geography. Native American Bank, for example, only has physical offices in Denver and Browning, Mont., but it is considering projects on Native lands throughout the United States, Ogaard says.

“Everything from office buildings to healthcare centers; it simply depends on what the need is,” Ogaard says. “Healthcare seems to be a significant focus these days, and we’re involved in clinic expansions, an elder care facility and other types of healthcare improvements that are going on reservations throughout the country.”

“As we do particular projects and talk to tribal leaders throughout the country, we’re asking them what is it that they need and how can we help with that need. It’s not simply a transaction for us; it is building a relationship.”

— Tom Ogaard, Native American Bank

A financial literacy foundation

Another important role Native American banks play is helping residents of their communities become financially savvy consumers.

Ogaard says that many tribal entities and individuals have not previously had access to financial services and may be intimidated by the prospect of approaching a bank. To help alleviate that, Native American Bank created a section on its website called Finance 101, which provides a structured set of lessons on topics ranging from building a financial foundation and buying a home to preparing for retirement.

“We’re just trying to take some of that mystique out of it and let them know that it’s not as difficult as it may appear,” Ogaard says. “And certainly, from our perspective, it’s a conversation that we want to have with them. Then, as we do particular projects and talk to tribal leaders throughout the country, we’re asking them what is it that they need and how can we help with that need. It’s not simply a transaction for us; it is building a relationship.”

Pape also believes in the value of face-to-face financial education. Chickasaw Community Bank hosts workplace education for employees of the Chickasaw Nation, and bank staff attend tribal events to educate members about home or commercial loan programs.

“We try to be involved with the family of companies owned by Chickasaw Nation and educate employees of those entities on programs that may be available to them as Chickasaw employees and/or as Native Americans in general,” Pape says. “And we are sponsoring an event to do family personal financial education nights and seminars at the Native American charter school.”

Native American communities face many financial and social struggles, from inadequate housing to high unemployment to financial illiteracy. Fortunately, the community banks that serve them help address those issues and aid them in realizing their potential.

“Lumbee Guaranty Bank was formed specifically to serve the underserved Native population,” Chavis says.

“And I think, in fulfilling our mission over the last almost 51 years now, we have definitely made a difference in the lives and financial well-being of our Native folks here, as well as in the communities that we serve.”

CDFI and MDI grants help Native American banks

Grants for Community Development Financial Institutions and Minority Depository Institutions, such as money from the Emergency Capital Investment Program, have helped Native American banks serve their communities.

“We received a significant amount of capital through the Emergency Capital Investment Program,” says Tom Ogaard, president and CEO of Native American Bank in Denver. “I think it’s going to have a transformational effect on the bank and our ability to support Indian country and what we can do to bring jobs and sustainable economic opportunity within Indian country.”

Serving the whole community

Native American banks are primarily owned by Native Americans, and most of their customers come from those communities, but they do not typically restrict their services to Native Americans. In fact, Lumbee Guaranty Bank in Fayetteville, N.C., encourages people who are not members of the Lumbee tribe to bank with it by incorporating a tagline in its marketing: “A Bank for Everyone.”

“We’re extremely proud of why the bank was founded and our original mission,” says Kyle Chavis, CEO of Lumbee Guaranty Bank. “But sometimes that’s a little bit of a barrier to folks, and their first question is, ‘Can I bank with you if I’m not a Native?’ And so, we have to really be diligent about our marketing efforts, especially in communities that are on the periphery of our footprint, to get that message out that we’re a bank for everyone.

“Again, we’re locally owned, we’re Native owned, we’re proud of who we are, but we’re a bank for everybody.”

CRA changes affect native-owned banks

Recent proposed changes to the Community Reinvestment Act may affect lending on Native lands, says Mickey Marshall, director of regulatory legal affairs for ICBA.

“The new interagency proposal would recognize activities in Native land areas for CRA credit on the proposed Community Development Financing Test when those activities are ‘related to revitalization, essential community facilities, essential community infrastructure, and disaster preparedness and climate resiliency that are specifically targeted to and conducted in Native land areas,’” Marshall says.

“This new definition broadens the geographic eligibility for earning CRA credits in Native land areas, while still keeping a focus on ensuring that loans and investments are targeted towards the benefit of low- and moderate-income residents.”

Subscribe now

Sign up for the Independent Banker newsletter to receive twice-monthly emails about new issues and must-read content you might have missed.

Sponsored Content

Featured Webinars

Join ICBA Community

Interested in discussing this and other topics? Network with and learn from your peers with the app designed for community bankers.

Subscribe Today

Sign up for Independent Banker eNews to receive twice-monthly emails that alert you when a new issue drops and highlight must-read content you might have missed.

News Watch Today

Join the Conversation with ICBA Community

ICBA Community is an online platform led by community bankers to foster connections, collaborations, and discussions on industry news, best practices, and regulations, while promoting networking, mentorship, and member feedback to guide future initiatives.