An upward slope can bolster market values.

Jim Reber: Rolling With the Curve

May 16, 2024 / By Jim Reber

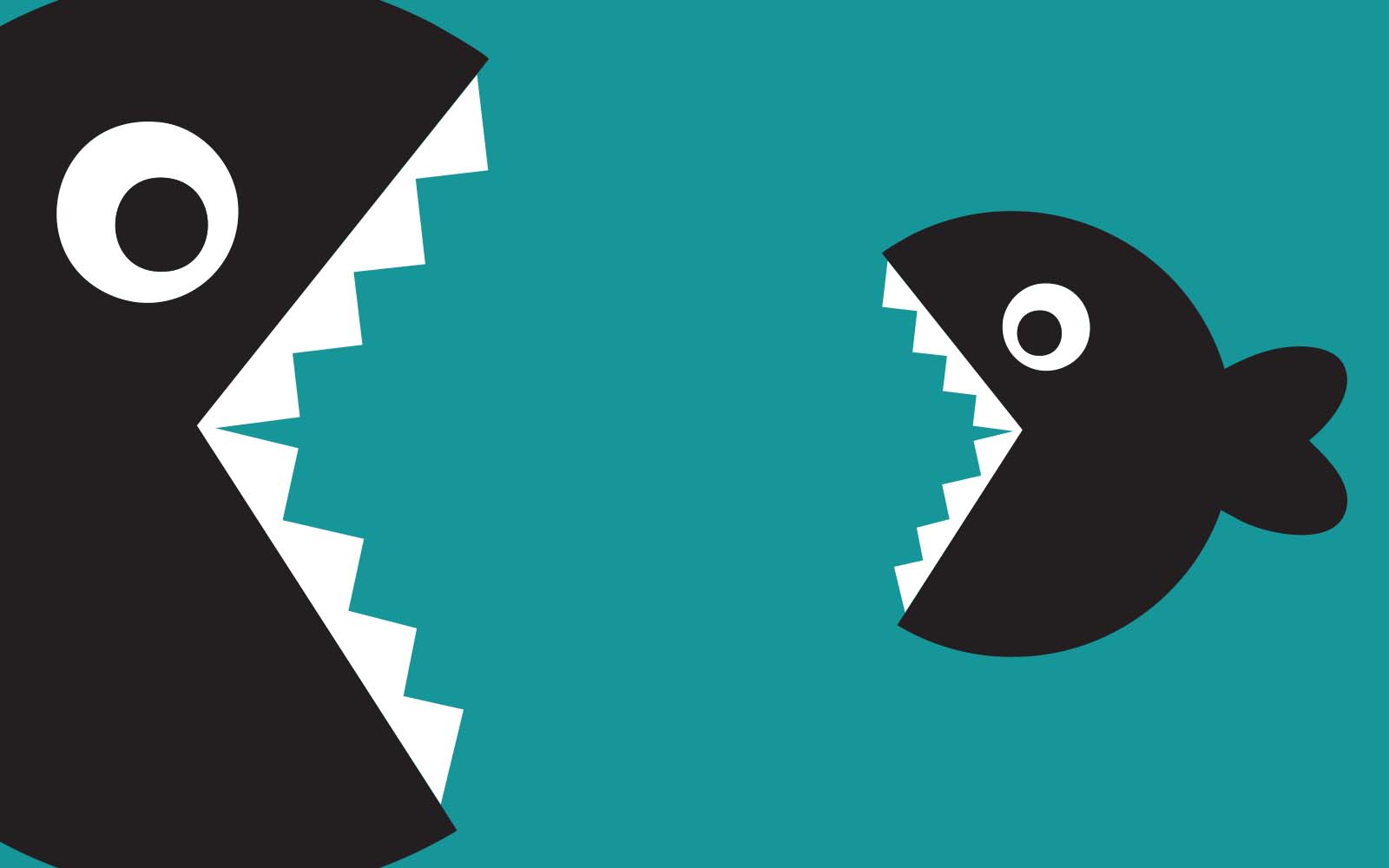

An upward slope can bolster market values.

As we lurch ever closer to the much-anticipated first rate cut by the Fed, it dawns on me (and perhaps you) that it’s been nearly two years that long rates have been lower than short ones. This is a record stretch of time for an inversion. It has presented rate risk managers with all kinds of conundrums, and lenders, portfolio managers and deposit gatherers with a bunch of headaches.

Assuming we’ll have some normal curve shape soon, I’d like to go through some fundamentals about how this affects a community bank’s market values and earnings. In the vernacular, it is the phenomenon known as “rolling down the curve,” and it represents the natural order of the debt security universe.

Shake, rattle and roll

There’s plenty of imagery and literature that describe rolling. The Army’s caissons keep rolling along—same with Old Man River. Jelly Roll and Jelly Roll Morton, two separate people, are musicians of very different genres. Those who have changed jobs recently perhaps have rolled over their 401(k)s. Thunder can roll, as can hills and waves in the ocean.

As it pertains to fixed-income investments, a given instrument can see its market value increase just with the passage of time, given several conditions.

The main ingredient is that short yields are lower than longer ones. Another is that “spreads”—which in this context means the additional yield an investor earns over and above a similar-maturity treasury—don’t widen after the bond is purchased. If these two criteria are met, that bond will roll down the curve, and its market price should increase.

Three years ago, just 1% of bond portfolios consisted of treasuries; now, that number is fully 10%. Treasuries are the best example of non-callable bonds, as none can be redeemed early.

Applying it to you

There are several reasons why this matters. Community banks’ bond portfolios are still underwater; as of the end of March, the average unrealized loss was 11% of face. Large portions of these portfolios have plenty of room to increase in value given a secular drop in yields and a resumption of a positively sloped curve.

Again, there are several reasons for this. The first is that a bond that’s worth 85 cents on the dollar, which perhaps was purchased three years ago, can jump in price even if there are embedded call features. This describes a lot of mortgage-backed securities owned by community banks. It’s been well documented that the record-low mortgage rates of 2020 and 2021 spawned plenty of pools with coupons as low as 1%, and borrower rates that begin with a “2” handle.

In addition, as discussed last month, there is a larger cohort of non-callable bonds in bank portfolios than in the past. Three years ago, just 1% of bond portfolios consisted of treasuries; now, that number is fully 10%. Treasuries are the best example of non-callable bonds, as none can be redeemed early—hence their appeal in what investors sense are higher‑than-normal rate periods.

Given these conditions (in other words, large positions of bonds with market values well below par, and larger positions of “bullets”), community banks’ portfolios are well positioned for their market values to spike higher.

Practical example

First, some historical perspective. From 1980 to the present, the average rate on overnight fed funds has been 4.39%, the two-year treasury 4.79%, and the 10-year treasury 5.68%. The average slope on the “2-to-10s” is 89 basis points, or 0.89%. Each year, therefore, the average market yield drops about 11 basis points.

For a four-year bond on this normally sloped curve, its progression over a 12-month period to a three-year term would improve the price about 0.33%, or $3,300 per $1 million face. That may not sound like much, but remember that math probably applies to the entire portfolio in 2024, as explained above. And, though we’re still inverted at the moment, there are plenty of periods in which the slope, particularly at the shortest end of the curve, is steeper than average. That would help the math of the roll.

It would, of course, be folly to predict when we’ll be finished with this abnormal yield curve shape. It’s also time to remind readers that an upward-sloped curve has embedded investor expectations for higher rates in the future. That means, by extension, a positively sloping curve is a really poor predictor, as rates have generally fallen in the last 40-plus years. In spite of these limitations, your collection of bonds is likely poised to, as Steve Winwood would say, “roll with it, baby.”

Education on Tap

Balance sheet webcast in May

ICBA Securities and its exclusive broker Stifel will host their Quarterly Bank Strategy webinar on May 9 at 1 p.m. Eastern. Several strategists and economists will make presentations, and up to 1.5 hours of CPE are offered. For more information and to register, contact your Stifel rep.

Virtual bond basics upcoming

Stifel will again offer a virtual bond school June 11–13 each day from 1–3 p.m. Eastern. Concepts such as rolling down the yield curve will be discussed. Up to nine hours of CPE are offered. Be looking for announcements this month.

Subscribe now

Sign up for the Independent Banker newsletter to receive twice-monthly emails about new issues and must-read content you might have missed.

Sponsored Content

Featured Webinars

Join ICBA Community

Interested in discussing this and other topics? Network with and learn from your peers with the app designed for community bankers.

Subscribe Today

Sign up for Independent Banker eNews to receive twice-monthly emails that alert you when a new issue drops and highlight must-read content you might have missed.

News Watch Today

Join the Conversation with ICBA Community

ICBA Community is an online platform led by community bankers to foster connections, collaborations, and discussions on industry news, best practices, and regulations, while promoting networking, mentorship, and member feedback to guide future initiatives.