The securities portfolio serves a multifaceted role on bank balance sheets. The relative rank of priorities varies somewhat from institution to institution, but the list of goals and objectives almost always features a combination of liquidity management, interest rate risk positioning and income.

These objectives are often in conflict with one another. While income is rarely listed as the top priority, most portfolio managers still spend an awful lot of time focusing on it. Successfully navigating these conflicts is what makes portfolio management an art rather a science.

This issue’s column focuses on the portfolio’s role in managing interest rate risk. The portfolio is often a relatively small portion of the balance sheet—averaging approximately 20% of assets for community banks. But because management teams have input on building the portfolio, it plays a pivotal role in balancing out the interest rate risk profile for the broader institution.

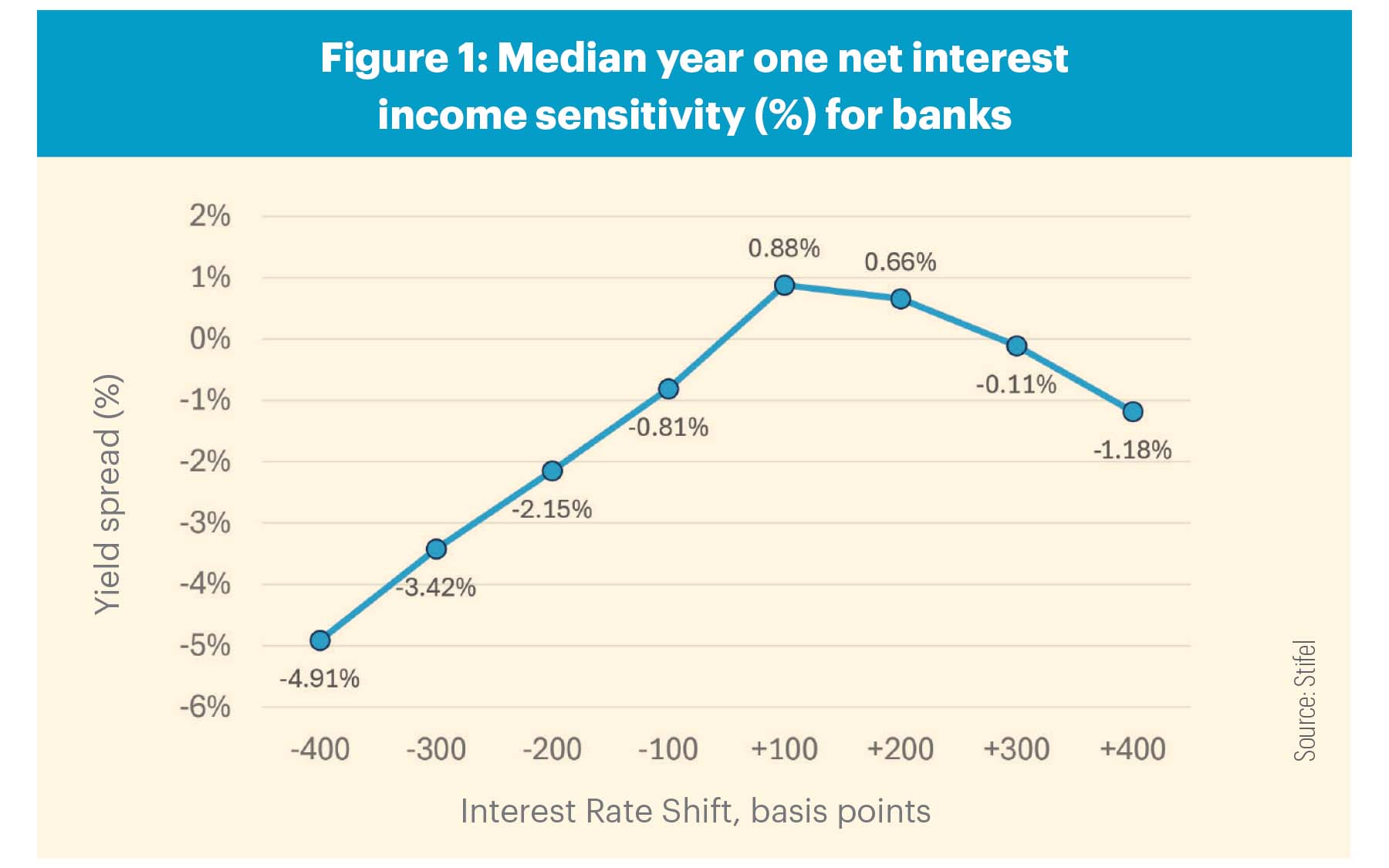

Stifel’s asset-liability team runs interest rate risk models for more than 200 banks each quarter, and aggregated statistics from their latest run—shown in Figure 1—indicate that median bank sensitivity for net interest income (NII) is slightly skewed toward being asset‑sensitive.

This means that the trajectory of NII moves in the same direction as interest rates, so if interest rates across the yield curve rise by 100 basis points (1.00%), net interest income increases along with it. Similarly, if interest rates fall by 100 basis points, NII declines. The reverse is true for an institution that is liability-sensitive.

Asset-sensitive interest rate risk positioning is fairly common across the community banking space, and so is an outsized exposure to severe declines in interest rates. As evidence of this, note how the magnitude of the median NII decline in the -200 scenario is considerably larger than the NII change in the +200 scenario. To put it another way, a 2% decline in interest rates hurts NII far more than a 2% rise helps it. This creates an interest rate risk profile that is both asset-sensitive (assets reprice faster than liabilities) and negatively skewed toward falling rates (rates-down hurts more than rates-up helps). Multiple factors influence why this happens, but to the delight of everyone reading this column, I’ll leave that as a topic for another time.

The key point is that the community banking industry, in general, faces considerably larger challenges when rates fall than it does when they rise. This is especially true if the move towards lower rates is accompanied by deteriorating asset quality, as this creates a rather unpleasant double whammy of declining income and increasing expenses.

As a result, management teams spend quite a bit of time thinking about ways to protect against a severe decline in interest rates. Because it can be difficult to address this risk through lending or deposit-gathering efforts, many of these concerns filter into conversations about the investment portfolio. This is where the conflict between portfolio objectives starts to come into play.

Insurance is expensive

The natural profile for protecting against severe declines in interest rates is some form of bullet or bullet-like cash flow that does not allow for early repayment of principal (or, at a minimum, pushes call dates several years into the future). Fits for this include Treasury notes, non-callable agency debentures, agency commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), municipals and corporate bonds.

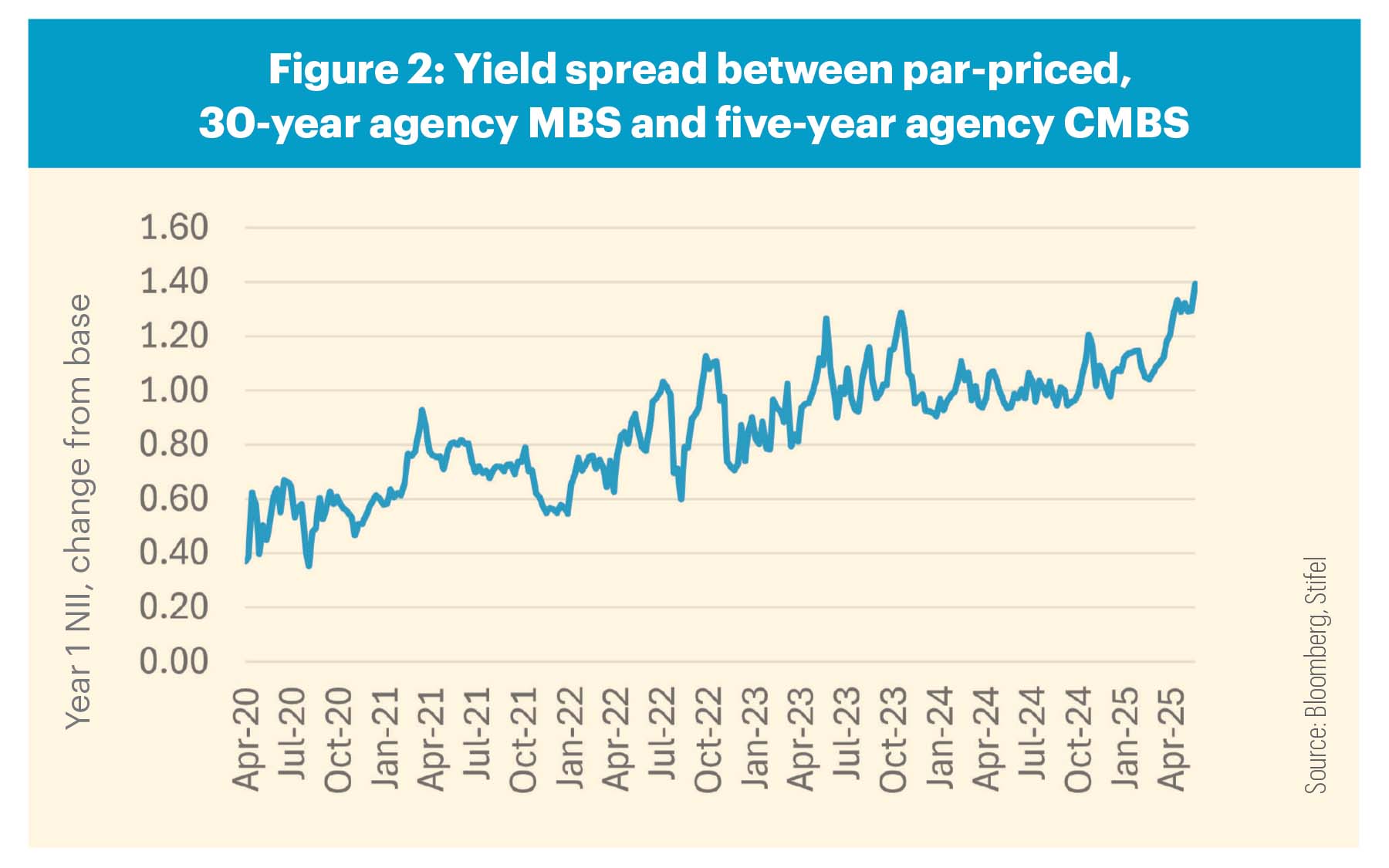

Though municipals and corporates have their place in community bank portfolios, this discussion will focus on agency CMBS to keep both credit quality and duration positioning comparable to other portfolio holdings. Treasuries and agency bullets also fit here, but agency CMBS (think Fannie Mae DUS or Freddie Mac K-certificates) offer similar cash flow profiles with better yields than either—so any conclusions will also apply to those sectors.

Figure 2 compares the yield on par-priced 30-year agency MBS versus agency CMBS with comparable duration. It shows that, at nearly 140 basis points at the time of writing, the spread between the two is the largest it has been in over five years. This generally indicates that demand for a “pure play” form of protection against severe rates-down moves is robust. If agency CMBS doesn’t quite hit yield bogeys, they can be paired with higher-yielding alternatives to increase weighted average purchase yield to an acceptable level.

However, if that cost seems too high, an alternative to consider is agency MBS or agency collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) featuring collateral coupons below current market levels. Though it can be difficult to generalize given the wide array of available coupons, structures, and collateral characteristics, deep-discount agency MBS/CMOs live somewhere in the gray space between current-coupon MBS and agency CMBS, making them a viable candidate for portfolio managers interested in providing some level of rates-down protection while generating yields of roughly 5.00% or higher.