After a long history of systemic economic oppression, Black-owned banks are playing a key role in improving the economic fortunes of their communities. We asked both community bankers and their customers about what this positive change looks like, as it was in the past, as it is in the present and as it will be in the future.

Success stories of Black-owned banks and their customers

0222 Black Owned Bank Sucess 2k

February 01, 2022 / By Roshan McArthur

After a long history of systemic economic oppression, Black-owned banks are playing a key role in improving the economic fortunes of their communities. We asked both community bankers and their customers about what this positive change looks like, as it was in the past, as it is in the present and as it will be in the future.

OneUnited Bank

Boston, Miami & Los Angeles

Ask president and COO Teri Williams how OneUnited Bank—the largest Black-owned bank in the country—came into being, and she’ll tell you its story can’t be told in isolation. The community bank, originally called Unity Bank & Trust, was formed in Boston in 1968, the year Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. After years of segregation and discrimination, Williams says, the four banks that make up OneUnited today (one in Boston and three others in Miami and Los Angeles) existed for a simple reason: African Americans couldn’t get financial services from white-owned banks.

Over the years, the four banks joined forces to pool resources and invest in technological growth, but the $700 million-asset bank’s mission remains the same: to address the discrimination that low-income, especially Black, communities face.

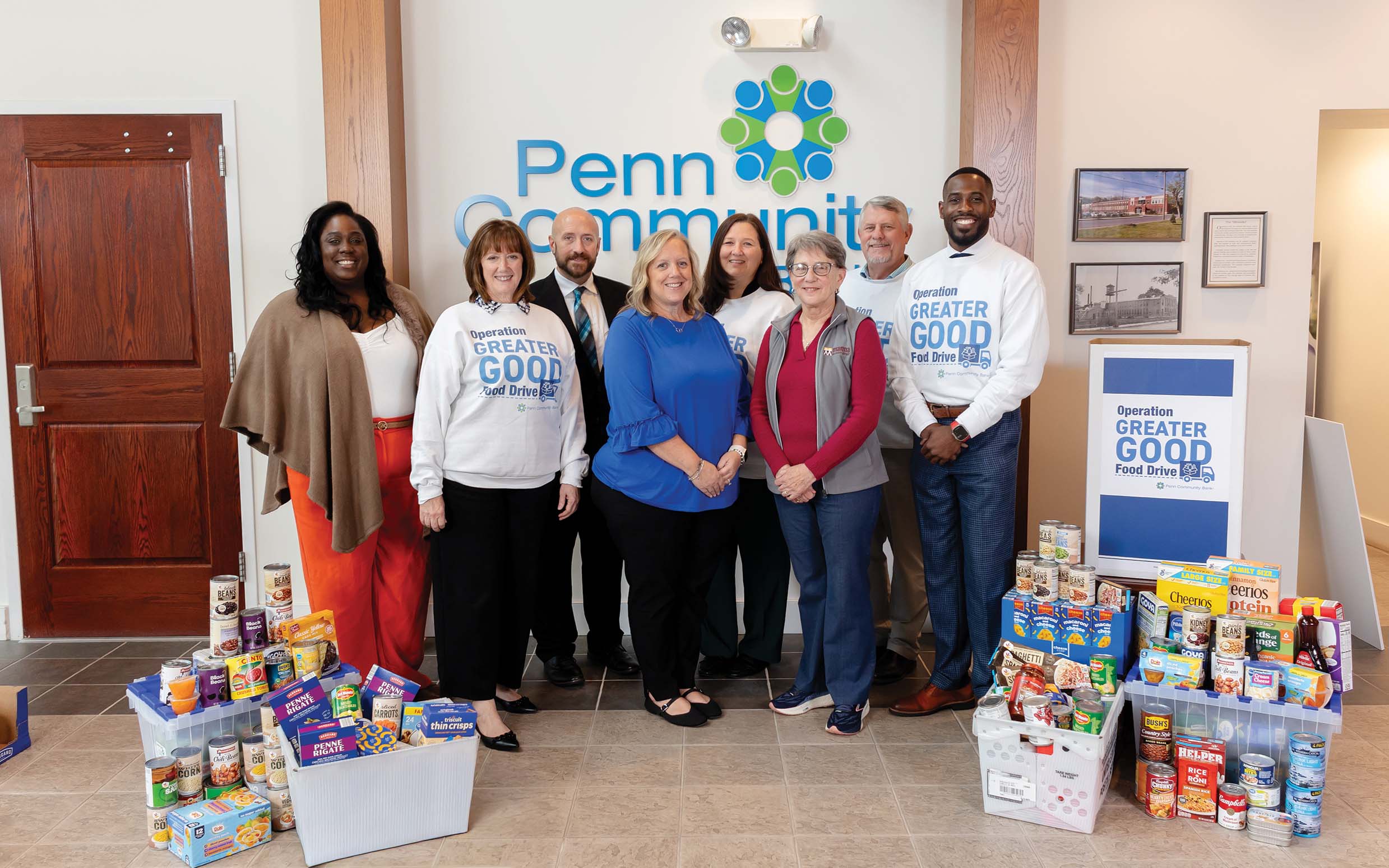

OneUnited Bank president and COO Teri Williams with volunteers at a holiday food distribution event in partnership with local charity Joshua’s Heart Food Pantry. More than 200 families each received a trunkload of food. Photo courtesy OneUnited Bank

Williams believes there has been considerable progress since 1968—with reservations. “It used to be that we couldn’t get a mortgage at all,” she says, “and now we can get a mortgage but, most of the time, not at the rate we deserve. It used to be that when we came into a bank, we felt unwelcome. Today, it’s more discrimination based on the amount of money that you have. Not to say that Black people with money don’t face it, too, but it’s become more economic, with high minimum balance requirements and other things that confront Black and white folks who don’t have a lot of money.”

OneUnited takes a broad approach to solving this problem, offering products like secured cards to help build credit, and second-chance checking for customers who have previously been rejected for accounts.

“We see our role as being, for lack of a better term, a beacon of hope.”

—Teri Williams, president and COO, OneUnited Bank

The bank takes its mission outside the community bank’s walls, too. Five years ago, for example, it helped found the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts to advance the economic well-being of Black people after a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found that the median net worth of nonimmigrant Black Bostonian families was only $8—not a typo—compared with white families’ $247,500.

“That’s not right, and we have to adjust it,” Williams says. “We see our role as being, for lack of a better term, a beacon of hope. It’s important for us, not just the Black community, but for everyone, for America to know that we’ve come a long way in a short period of time. We have more work to do, but it’s not all doom and gloom.”

“Dispelling [racial wealth gap] myths is … important, because you can’t solve the problem if you don’t understand the problem.”

—Teri Williams, OneUnited Bank

Myth busting

“We also try to dispel myths,” Williams adds. “The racial wealth gap didn’t happen because Black folks don’t know how to save or because we’re not good with our money. There were systemic challenges that were put in front of us that have resulted in us having less wealth. So, dispelling those myths is also important, because you can’t solve the problem if you don’t understand the problem.”

Customers open accounts at the Black Money Matters event at OneUnited’s Los Angeles branch. Photos courtesy OneUnited Bank

In 2006, OneUnited became the nation’s first Black digital bank, partly because of a need to manage geographically diverse branches but also to attract the next generation of customers. It was an early strategic move that has paid off, most notably in 2020, when the bank doubled in size. There were two reasons for this, Williams explains. One was the pandemic, when going to a branch wasn’t an option. The other was an increased awareness of systemic racism in the United States.

“People wanted to move their money to an institution that had a social activist agenda,” she says. “We had been supporting Black Lives Matter and the social justice movement for years, not just in 2020, so people came to us for that as well.”

Today, OneUnited boasts customers in all 50 states and describes itself as “unapologetically Black,” stating on its website, “We want you to stand up and represent. We want you to be part of the movement—to BankBlack and #BuyBlack—to demonstrate our economic power. Yes… Black Lives Matter. Black Money Matters.”

Customer story

Willie Simmons & Darrin Jenkins

Public Security, Inc., Los Angeles, Calif.

It’s a testament to the success of OneUnited that Willie Simmons and Darrin Jenkins, co-owners of Public Security, Inc., in Los Angeles, don’t see the bank as minority focused. Public Security, Inc., which provides security personnel for clients across southern California, has been with OneUnited for 25 years now.

With years of experience in law enforcement, Simmons and Jenkins wanted to create a work environment where officers were treated fairly and compensated well for their work, and OneUnited has helped them pursue this goal. They received a line of credit to build the business and recently had the bank’s help securing a PPP loan. Their employees, the majority of whom are African American, go to OneUnited to cash checks, and its bankers have helped them open savings accounts.

“They’ve just been a good partner for our firm,” Simmons says. “Any of the banking services that I’ve needed, they’ve been able to take care of.”

Photo courtesy OneUnited Bank

Thunder & Enlightening: The OneUnited Mural Project

In July 2015, OneUnited Bank unveiled a mural on the wall of its branch in Liberty City, Miami. Created by local artist Addonis Parker and 21 inner-city students from nine Miami high schools, it’s a bold portrayal of racism and protest. The mural features images of shooting victims Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, as well as the devastating church shooting that had just taken place in Charleston, S.C.

“That project was a turning point for us,” says OneUnited president and COO Teri Williams. “People started to come into the bank who had never been in a bank before in their lives. They saw that mural and they were like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s a reflection of me, what is this?’

“We used to position ourselves as a community bank that happened to be Black,” she adds. “And in 2015, when we did that mural project, we said, ‘Nope, we are a Black bank, and we are going to speak in our authentic voice.’ We’re not going to just try to be a bank that has a Black face. We are going to be who we are. Because by speaking in our authentic voice, we will be able to connect with our community in an authentic way.”

Photo courtesy Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Company

Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Company

Nashville & Memphis, Tenn.

Founded in 1904, Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Company is the oldest continuously operating African American owned and operated bank in the United States. The $127 million-asset bank survived everything the 20th century could throw at it, including the Great Depression—a fact that president and CEO Sergio Ora attributes to the will and determination of its founding fathers, nine African American businessmen from Nashville.

The founders saw the inequity that existed in the community, and each contributed $100 to found the community bank—originally called One Cent Savings Bank—to encourage neighbors to start saving, even if they only had a few pennies.

“We are a mission-driven institution,” Ora says. “We focus on the underserved, the overlooked and the neglected, and on the betterment of communities that we operate in and that we call home, both here in Nashville and in Memphis.”

Jeffery W. McGruder II, Citizens’ chief relationship officer, explains that these were men who understood the needs of the community and belonged to the church that until that point had been the community’s main lender. He credits one of the founding families with keeping the bank going when times were tough.

“The family that had the majority ownership of this bank also had a thriving business going on,” he explains. “The Boyd family were the founders of the R.H. Boyd Publishing Company that printed media, hymnals, anything church-related for Black churches across the country. I’ve heard stories of the original Mr. Boyd putting money in the windows of the bank during the Depression, so people would know that there hadn’t been a run on the bank.”

Refresh and renew

Today, Citizens is fighting gentrification in favor of revitalization. The community bank’s main office is located in a district once known for extreme poverty and the highest concentration of prisoners in the U.S. per capita, but it’s now ripe for redevelopment.

“The bank’s role now is to preserve as much of the economics in the community as we can,” McGruder says. “One of the stories we’re trying to get out to those who own land in the community, who own businesses, is this notion of the money multiplier. It’s to tell the story of keeping your deposits and your capital gains from your real estate in this district, and also to educate them that when you put those gains into our bank, our mission will increase the net worth of African Americans, create jobs and participate in the organic growth in Nashville.”

Ora adds, “Revitalization is when you stay where you are, and you put your money back where you are. And that basically creates an upward spiral of economic growth and wealth creation. That’s what we want to achieve.”

This means focusing on funding small businesses and developers who are creating affordable housing, as well as helping formerly incarcerated people get full-time work and buy property in the neighborhood. That’s an invitation that’s open to everyone. “I don’t want Citizens to just be known as a Black bank,” says McGruder. “I just want to be known as the community bank that’s Black-led or minority-led. We want everyone’s business.”

Customer story

Laurence Plummer Sr.

Plummer Financial Services, Memphis, Tenn.

Financial adviser Laurence Plummer Sr. was purchasing a property in 2005 but still had his current home on the market. It was one of those transactions that required speed and finesse, but he had trouble finding a bank that would work with him.

“I actually gave three banks a shot at getting it done,” he says. “But when I called Citizens, they basically told me, ‘Let’s get it done, what do you need us to do?’ I told them exactly what the situation was, and I promise you within less than 24 hours I had an, ‘OK, let’s go, we can get this taken care of for you.’ So, it was a seamless transaction.”

Plummer recalls one of the first things Citizens president Sergio Ora told him: that they were not a transaction bank, they were a relationship bank, and Plummer has seen this in action countless times.

“In the African American community, a lot of times they’re not privileged to have banks that will go to bat for them,” he says. “I’ve referred people to the bank, and they’ve given me phone calls back saying, ‘Thank you so much, they were easy to work with, they took care of me, I got my mortgage, I got my car financed.’ It’s just a major, major plus to have a bank that they can call and feel like they have some type of client relationship with.”

Customer Story

Larry Turnley

Self-employed businessman, Nashville, Tenn.

In 2016, Larry Turnley was released from prison after serving 20 years for a drug offense. The Nashville native returned home determined to rebuild his life—one part of which was resuming tax payments on a home he had bought in his cousin’s and grandmother’s name almost 30 years ago. He worked several jobs, saving $100,000 in five years, but when he approached a bank about a mortgage, they told him he didn’t have enough credit history.

In the meantime, Turnley had also become a community activist. He hosted an annual Thanksgiving Day Dinner and a Christmas Coat Drive for local families. He worked with Gideon’s Army, a local group whose mission is to eliminate the root causes of the “prison pipeline” and put children on the path to success. And following the March 2020 tornado that badly affected north Nashville, he met Jeff McGruder from Citizens Bank when they were both helping with disaster relief.

Turnley asked McGruder about the home he was trying to get a mortgage for. “He knew the work that I have been doing here in the Nashville community,” Turnley says, “and he was like, ‘Man, I’ll be honored to help you because of the great work you are already doing.’ I was like, ‘I should have spoken with you earlier.’”

Together, they secured a commercial loan by turning the property into rental units and setting Turnley up with an LLC. Today, he is converting the house and has his own junk removal and hauling business. McGruder even introduced him to his first customer.

“It’s been life changing,” Turnley says. “He’s like a mentor for me because of how he’s basically grabbed my hand and linked me up with the small-business people at [Tennessee Small Business Development Center].”

Through a class at the business center, Turnley learned how to set up a business plan and how to bookkeep. “It’s hard in this day and time for people to embrace you and open up, and just guide you,” he says. “I’m appreciative of [McGruder] and the bank for believing in me.”

Core Strength

InnerG Juice & Yoga opened in July 2021 in an old supermarket in north Nashville, bringing healthy juices and yoga practice to an underserved community and food desert. But getting it started wasn’t easy. Jeff McGruder at Citizens Bank remembers a young professional, Nielah Burnett, approaching them for a loan. “She just needed someone to take a chance on her, to give her $50,000 on a line of credit, and maybe a term loan to help build out the store,” he says. “Through a discussion with her and a partnership we have with Tennessee Small Business Development Center, we got that money to her.”

Numerous regional banks turned down Burnett before she met with Citizens Bank. “I understood that she would not let this business fail,” McGruder says. “I knew personally where she was going was a great location, because I financed the project where she was a tenant, and I knew the landlord. I knew what other companies were coming in around it. That’s how understanding your customer and knowing your neighborhood makes a big difference.”

Subscribe now

Sign up for the Independent Banker newsletter to receive twice-monthly emails about new issues and must-read content you might have missed.

Sponsored Content

Featured Webinars

Join ICBA Community

Interested in discussing this and other topics? Network with and learn from your peers with the app designed for community bankers.

Subscribe Today

Sign up for Independent Banker eNews to receive twice-monthly emails that alert you when a new issue drops and highlight must-read content you might have missed.

News Watch Today

Join the Conversation with ICBA Community

ICBA Community is an online platform led by community bankers to foster connections, collaborations, and discussions on industry news, best practices, and regulations, while promoting networking, mentorship, and member feedback to guide future initiatives.